It’s remarkable that Alphamstone, with its population of under two hundred, can foster such a lively and true sense of community. Gone are the days when every little village had its own school – ours is now the Village Hall – with a house and mistress, and children walking through the lanes to lessons. Gone too is the pub, time-honoured refuge for the thirsty labourer (or the hen-pecked). There’s no shop where you can exchange gossip over sewing thread or potatoes (although Mary’s Trolley near the green does sell produce and plants in season). Many of the inhabitants work far from their homes, and at jobs which would have been incomprehensible to our forefathers. At the time of the 1841 census, there were 314 people registered here, a large number of them giving their occupation as agricultural labourer, although there was also a shoemaker, blacksmith, wheelwright, carpenter, carter, brickmaker and thatcher – almost the cast-list of a Thomas Hardy novel. The face of rural life has changed forever, but there is one village institution which has weathered more than the passing of centuries of custom – and that’s the church. While ‘The Church’ struggles with controversy and crisis, it’s in the village church that the everyday drama of life – birth, love and death and the rhythm of the turning seasons – is acknowledged and celebrated, giving people a sense of continuity and even a measure of immortality, with the marking of these human landmarks in parish records and on gravestones.

Alphamstone churchyard has one of those archetypally pastoral settings which inspire poets and painters. Its relatively elevated position – nowhere in Essex is exactly mountainous – allows it to contemplate a landscape of fields and woodland which probably hasn’t changed much in several hundred years. It’s one of the most peaceful spots imaginable, sloping gently away on each side, and it’s pleasant to wander in the long grass among its monuments. The church was built over a Bronze-age barrow, and you’ll find several sarsen stones which might have been of ritual significance around the area – even two built into a corner of the west wall. This was a holy place long before Christianity arrived, and the simplicity of the church emphasises its elementally sacred atmosphere. It was in the early 12th c. that a little stone sanctuary was built – probably just a nave with a small chancel and semi-circular apse. At this time it was under the jurisdiction of Waltham Abbey, and after the Dissolution of the Monasteries it passed to the Crown. Over the next centuries many additions and alterations were made – you can read more detail about the history in a little booklet available from a table at the rear of the church.

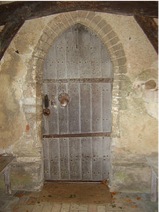

Some features remain from the church’s early days, including a blocked-up Norman window and a fine font, and a stone sedilia and piscina in the chancel. You enter the church now by the 15th c North porch – the door and its wonderful old handle also date from this time. However, in former times the main entrance would have been through the South porch, which has a particularly special aura – perhaps because it looks out to the open country beyond. Three 16th c bells in the 18th c belfry are still in use, although these are struck rather than rung nowadays, which makes a very different , more carillon-like sound.

Without a name until 1975, St. Barnabas was chosen because in mediaeval times there was a village fair and feast on the first Thursday in June. As St. Barnabas is the only saint with a nameday near this date, it seems likely that this might have been both the original dedication and the reason for the fair. Whichever came first, the embarrassing fact is that in 1776 the Alphamstone fair was banned for inciting “drunkenness, unlawful games and plays”. In the light of this, it’s rather amusing that the modern villagers always hold a grand fête on Bank Holiday Monday at the very end of May – old habits die hard, and though it hasn’t yet been banned, it’s certainly a very festive occasion!

We can trace Alphamstone’s rectors back to 1290, when Henry de Sutton was incumbent – there’s a board inside the church inscribed with the names. The most notorious of these was undoubtedly Nicholas de Gryce, who in the 1570s got into trouble with the law for repeatedly enclosing common land for his own use; more scandalous (and downright stupid, it has to be said) was his insistence that his maid had to share his son’s bed to save money – when she predictably became pregnant, he dismissed her and sent his son away… In 1800 another rector, John Gamble, must have sanctioned an extraordinary act of vandalism, as the mediaeval stained glass was systematically removed from the church, bundled up and sold on Sudbury market ‘for what it would fetch’. History doesn’t record why this happened, nor how much the sale raised, or, indeed, whether the church itself received anything from it. The fragments which remain in place are a small consolation.

Today the church is in quite good shape – the roof and the belfry were restored in 2005, and some structural work done inside. The unusual tapestry kneelers were designed and made by men and women from the village and depict local flora and fauna. The churchyard is regularly mowed and tended, and even those of us who are not churchgoers have a fierce affection and respect for this indomitable little building, steeped as it is in thousands of years of worship, prayer, joy and sorrow. In a very real sense it’s at the heart of Alphamstone.

One Reply to “Alphamstone Church”

Comments are closed.